Controller

The goal of a controller is to learn the brittle star how to use his body. We do this by using reinforcement learning (RL). RL consists of 3 important aspects, observations, actions and rewards. A brittle star will walk around in an environment, step by step. At every point in time, he has certain observations, like “the target is to my right”. Based on those observations, he will try to pick the action that will give him the highest reward. Once he has executed the action, like “step to the right”, he will receive the, in this case, positive reward he got from doing that action. Thus he can learn how to walk to a target, by maximizing the cumulative rewards.

QLearning

At the start of the project we began by following a tutorial about QLearning, to try to create a controller for a default brittle star. We ran against a few errors in this tutorial which were mostly related to typos and return type issues from typing the code from the videos. After finding the bugs, which was a tedious job that took watching all the video’s over and over again, we were able to fix the qlearn controller. This resulted in a simple qtable for our controller that had 3 actions (straight, left, right) for a simple morphology with two arms.

Implementation

We changed a few hardcoded things and added some extra features:

- define actions based on number of arms

- generate arm amplitudes based on number of arms

- define states to divide the z-angle equally among the number of actions

- gradually decreased the value of epsilon as average reward increased

Due to these changes we were able to easily change the number of arms to try different morphologies and different numbers of actions.

In order to make the progress during training trackable we added some extra features to the WandDB logger.

Result

We were able to create a good working controller by changing the epsilon value dynamically at runtime. At the end of every evaluate step, the epsilon values was recalculated by looking at the final reward. A high final reward resulted in a lower epsilon value for the next training loop and vice versa. The video below shows the final result of our qlearning for a default two arm morphology.

PPO

We now turned our attention to more complex reinforcement methods for our controller.

We chose for Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), since it is supposed to learn rather quickly.

We use StableBaselines as the framework for our PPO reinforcement learning.

This allows us to perform PPO without having to fully implement this ourselves. We use PPO with a mutli-input policy and a ReLu activation function.

This wasn’t very succesful, as this algorithm (and deep RL algorithm in general) are very sensitive and thus hard to get it to actually learn something.

What now?

Now we were ready to give the project some more thought and do some experiments. We’ll explain the 3 important parts of RL: observations, actions and rewards. And what we changed for the PPO to work

The observation space

We simplified our observation space in order to simplify the model input and to speed up the training process. Our observation space only contains a single parameter namely the normalized z angle towards the target. This is the angle between the fixed frontside (so not the front arm) of the robot and the target in a XY-plane. This means that the robot has no motion of its distance from the target, only a direction.

The action space

We tried to mimic a realistic brittle star, which doesn’t turn all that often. Instead it just elevates the arm closest to the direction it wants to go to and walks in that direction. It only adjusts a little bit along the way, so we tried to simulate this. We gave our brittle star the ability to change his front arm and walk into that direction. This would hopefully result in a brittle star that moves in a quick and very natural way, without the need to fully rotate when he wants to go in the opposite direction.

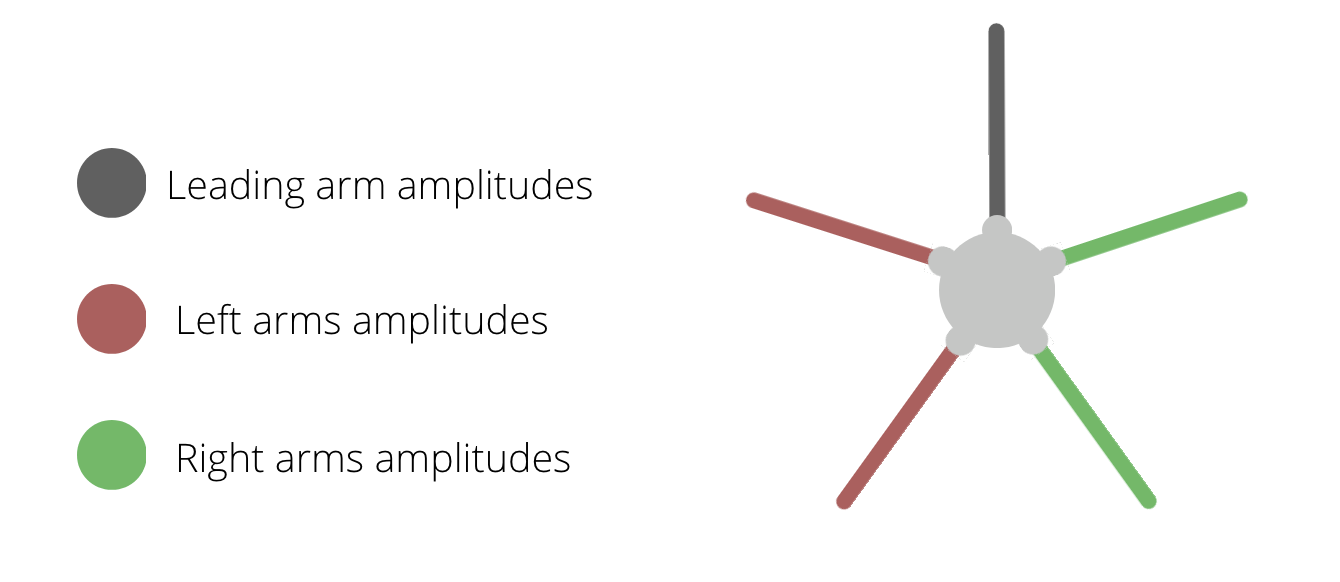

This means that our brittle star could use any one of its five arms as it’s leading arm. The goal would be for this leading arm to be lifted up, while the other arms make the robot move towards the direction of the lifted arm. We also added the ability to adjust it’s movement a little bit. So that he can slightly rotate to the left or slightly to the right (amplitudes).

The main part for this, is an interface we agreed upon with the morphology. This interface has 3 main parameters:

- the leading arm index

- the amplitudes of all arms to the left of the leading arm

- the amplitudes of all arms to the right of the leading arm

The leading arm index allows us to pick a new (elevated) front arm. And the amplitudes of the left and right side allow us to steer a bit when needed.

As we use a discrete set of actions, we can’t just let PPO estimate the amplitudes. Thus we defined some amplitudes ourselves and let the PPO choose from them. Per leading arm we added 3 choices for the amplitudes, one choice makes the brittle star walk in the direction of the leading arm, one turns slightly to the left and one turns slightly to the right.

In case you are wondering what exactly we mean by “leading arm”, below is a video showing this type of movement. This controller only had the ability to change the leading arm, there was no ability to adapt the amplitudes.

Rewards

Our reward functions needs to make the connection between our observed angle and a good action that should be rewarded. We do this by rewarding every action that places the robot closer to the target. This is simply done by returning a reward based on the difference in distance to the target after the action and before. In our original reward we also greatly rewarded our brittle star when it reached the target. However it turns out that PPO is not good at handling a non-deterministic reward function that over-rewards a certain state.

Our final reward function is simply the signed value of the square difference of the target distances.

Back to PPO

With these new changes, our PPO controller was able to sometimes learn something. What a relief! Time to improve it using other tricks than just the 3 main pillars of Reinforcement learning.

In our effort to create a succesful PPO controller we stumbled upon a series of difficulties. We will shortly describe some of the most important ones here.

training is very sensitive

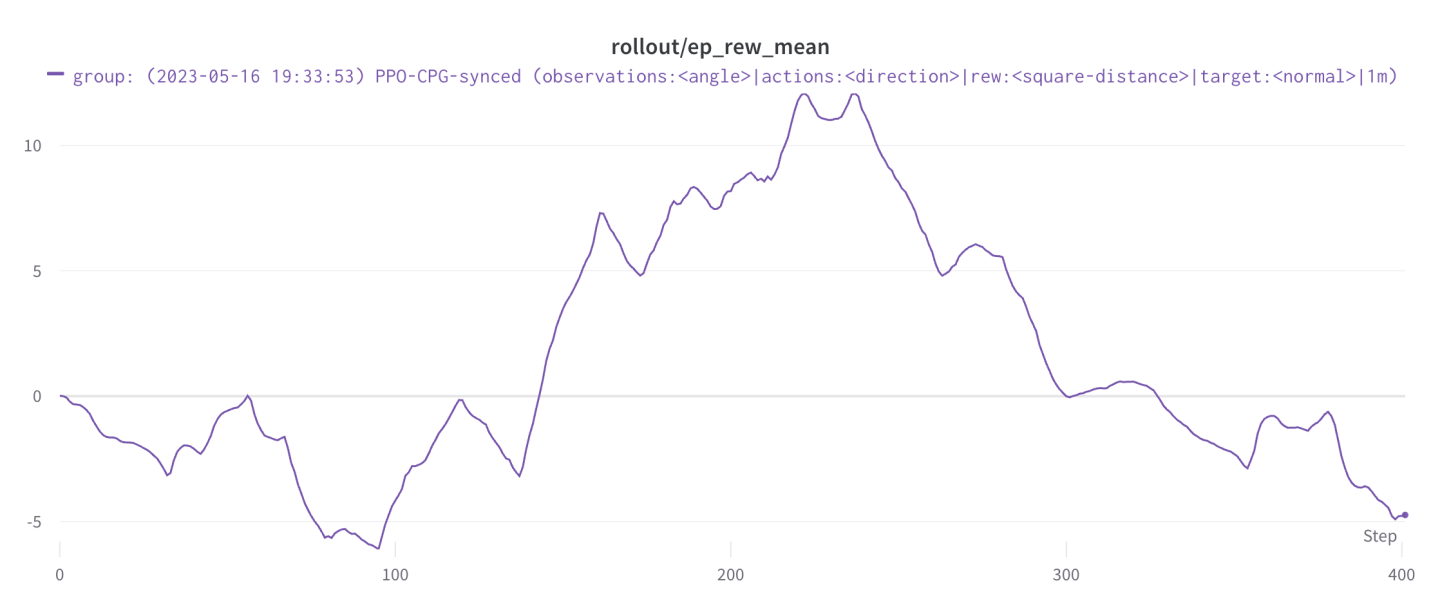

Right from the start of our first PPO training we noticed that it was very sensitive. The training reward was very unstable and did not always end on it’s highest value. In order to be able to compare different training settings we used longer training runs and went for a default of one million timesteps (2,5h of training time approximately).

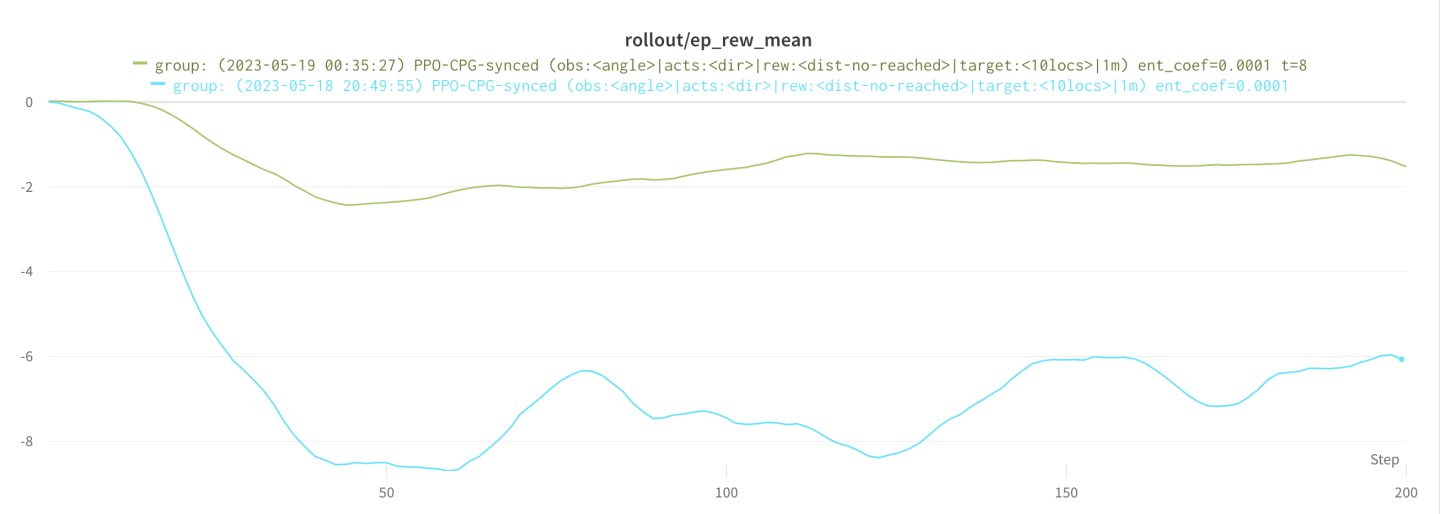

The graph below is a good representation of this unstable training, this was mostly due to the reward function that at the time still included the huge bonus reward when the brittle star reached the target (which PPO didn’t like).

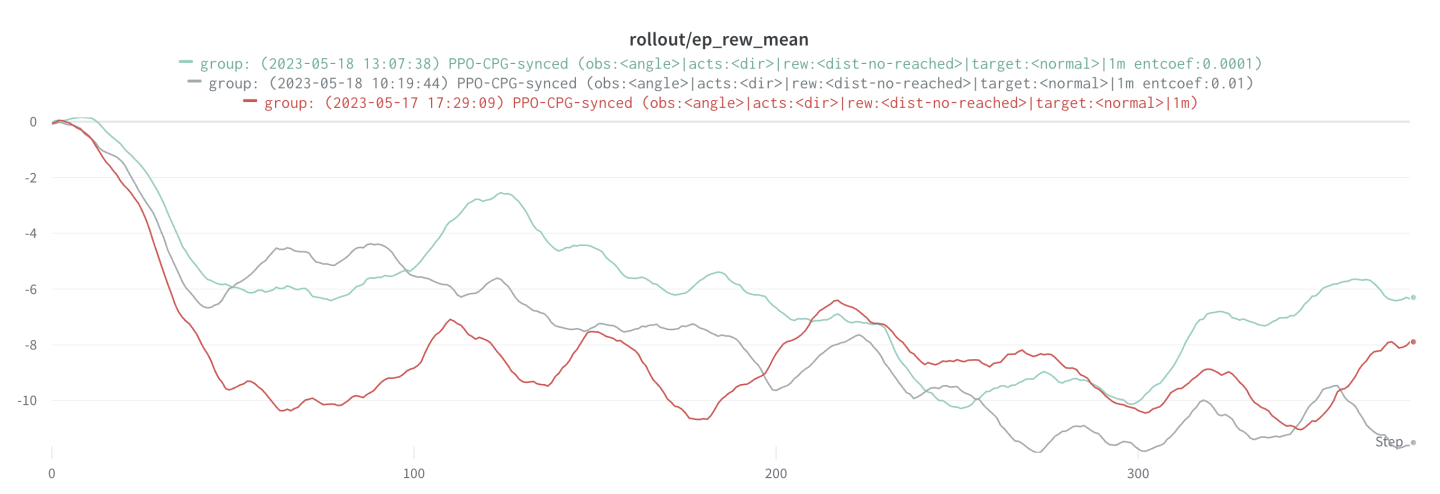

hyperparameters

The ppo algorithm from StableBaselines has an extended set of hyperparameters that can be tweaked to impact the training results. We started off with the default hyperparameters and experimented our way in to a good working result. We ran many tests, often with not very good results. We ended up changing the entropy coefficient for the loss function from 0 (red) to 0.0001 (blue). This improved our overall training performance as can be seen in the graph of the reward below.

We also ended up changing the n_steps, which was needed for a more discretized learning approach as will be described in the next section.

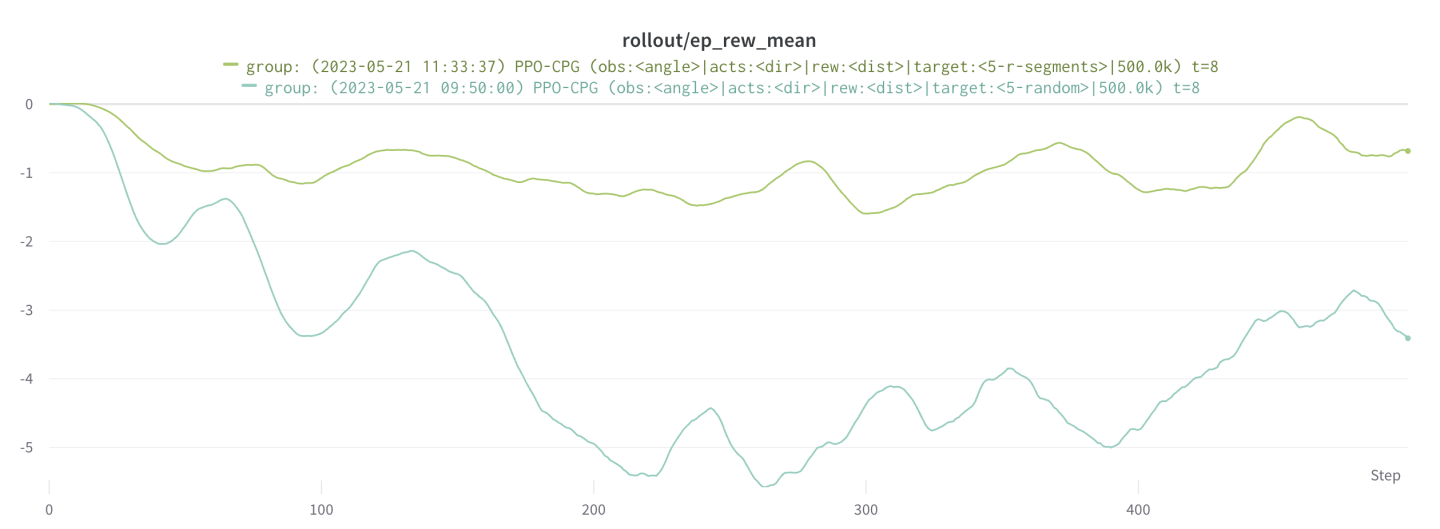

discretized locations for an epoch

The biggest reason why our PPO wasn’t able to give good results on an extended training run with a million timesteps was due to the way targets spawned during training. The environment created targets in a random fashion, the distance from the target was fixed at 5 but the angle was random. This meant that during training a target spawned randomly on a circle with radius 5 around the brittle star robot. Since the n_steps parameter of PPO was set at 2048 and the max runtime of a training at 20s, a single epoch would see only 4 target locations. It was thus possible that this epoch would see only targets in the same half circle or even the same quadrant leading to overfitting and unstable learning.

We fixed this issue by discretizing the target locations so that every epoch would see a full circle of targets. Therefore the n_steps parameter had to be calculated as a function of the simulation time and the number of target locations. This led to way better results and is by far our biggest improvement towards a good PPO controller. We experimented with various numbers of target locations and settled with 5 locations for our final result. The graph below clearly show the difference in random locations (blue) versus discretized locations (green) for every epoch. Not only is the reward value way higher at the end, it also has a way more stable trend.

One notable thing when adding these locations, is that the training time can increase by a huge amount. If you want to add more locations, let’s say 20 locations instead of 5. Then your total training time goes up by 4x if you wish to keep the amount of PPO-iterations the same.

simulation time 8s vs 20s

Another issue we stumbled upon was the fact that longer simulation times led to a more zigzaging robot. PPO is build to maximize the reward during its full simulation time, so if the simulation time would be longer than necessary for the fastest path it would induce creativity to rake up extra rewards. This is exactly what happened with our initial simulation time of 20 seconds. This created a controller that took a zig-zag path towards the target since more steps would mean more rewards.

By reducing our simulation time to 8 seconds, PPO learned to take a more direct path towards the target. Within this simulation time, the robot could almost never reach the target, however this was not necessary since no reward was given upon reaching it. In fact this is a good thing since our reward was the square of difference in distance towards the target, taking big steps towards the target resulted in big rewards. The path of maximum reward over the full simulation time was now the path straight on to the target, which was exactly our goal. This is clearly visualized in the following graph showing the PPO controller with a simulation time of 8 seconds in green versus one with 20 seconds in blue.

Results

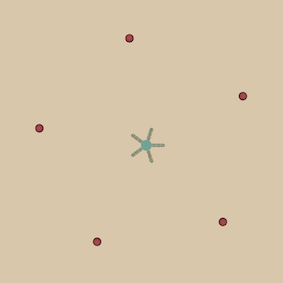

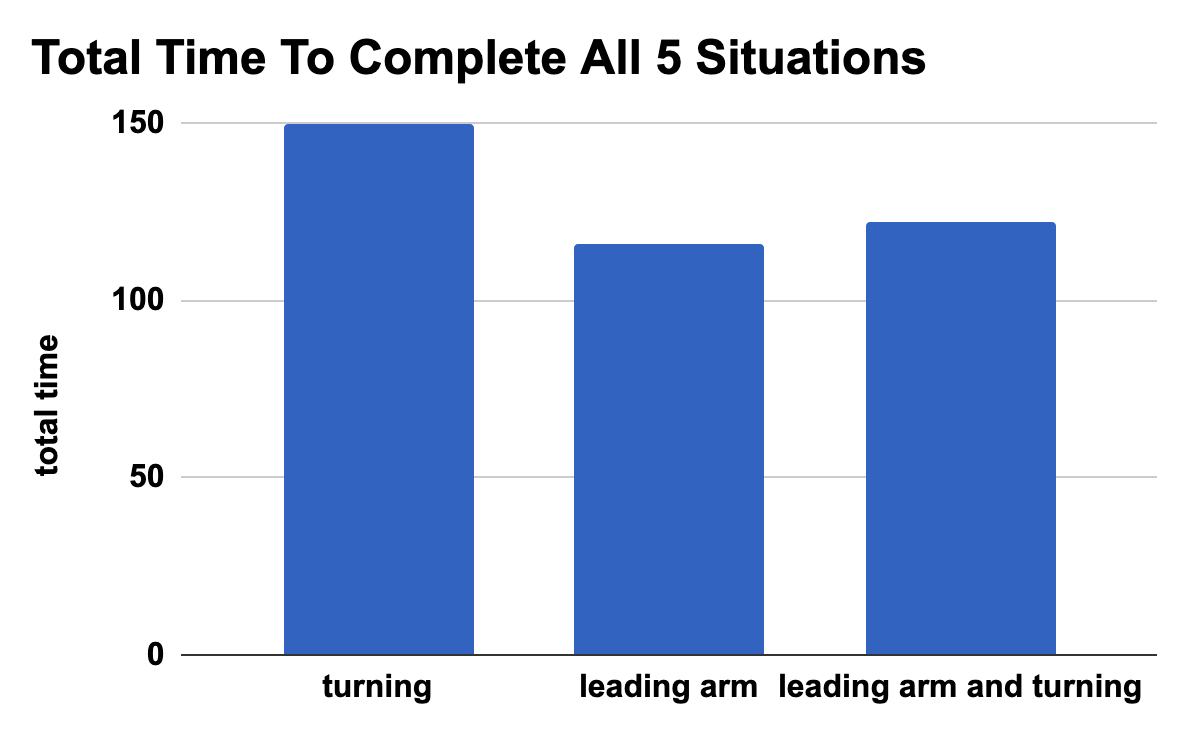

As our research is focussed upon the speed of the brittle star, our metric for comparison is mainly based on time-to-target, or how long it takes for the robot to reach the target. We made a few controllers having different abilities and compared them in 5 different settings. In total we compared 3 controllers, measuring the impact of adding a leading arm to a brittle star simulation on it’s time-to-target. The first controller, “turning”, could only turn, so he could not change his leading arm. The second controller “leading arm” could only change his leading arm and had to walk in that direction without turning. The (third) last controller, could do both. He had the ability to change his leading arm, as well as turn a bit to adjust it’s path. The 5 different settings are 5 targets well distributed around the robot like in the picture below.

We let each controller try to walk towards each of these targets and measured how long it took. The total time-to-target for each controller for all 5 situations, is shown below. The controller with the lowest score (lowest total time), is thus the best / fastest controller. We can see that the “turning” controller is always the slowest. This confirms our suspicion that a brittle star that can only turn, is in fact slower than one who can just change it’s direction at once, without the need of turning. It is clearly visible that the two controllers who do have the ability to change their leading arm, are faster. It is quite odd that the controller that has the ability to do both (change leading arm and turn) is a bit slower then the “leading arm” controller, who can’t turn / adjust it’s course. We think this might be due to the fact that it is harder to train, as it has a larger action space. But we’re happy to see it was a neck-by-neck race and it only got beaten by a few seconds (6 to be precise).

Discussion

Although we tested quite a bit and the controller steered the robot in the right direction most of the time, there were also times when the target was completely ignored and the brittle star went on a little adventure. But we believe we were able to show that adding the ability to change the leading arm, is a great boost in decreasing the time it takes for the brittle star to reach the target.