Environment

Design Philosophy

When working on the simulation environment, our central goal was to always be fully backwards-compatible. All of our changes and extra features are completely opt-in, and we never alter or remove existing parameters or functionality. This eases the process for the morphology and controller teams, as they don’t have to care about every single feature we want to add, and can choose to look at them when they want to, and feel ready to. This allows us to add as many features and as much flexibility as we want, without annoying the other teams. Any extra morphological component was added with a default value, so that existing morphologies and morphology specifications should not notice these changes.

In the case of morphological components this is extra important, because each added parameter complicates the entire structure of their project, and each added MuJoCo entity greatly impacts performance.

Similarly, adding defaults and making features opt-in makes it so that the controllers don’t break constantly, but they just keep functioning as normal. They can choose to adopt new features whenever they want to.

Robot Morphology

The morphology did not change a lot as opposed to our starting point, most of the changes are related to the tendons of the robot. Parameters for the amount of tendons, the stretch factor and contraction factor have been added. To place these tendons and configure their attachment points an equidistant point function has been developed.

This function generates points on a circle around a given position around a given axis. It is used for placing the arms, tendons and later on for the target locations. An important quirk of this function is that the first point can be set at an offset, the tendon start will always be at the top of the circle (at + π/2). This can be seen in the gif below.

The simulation environment also has an option to place the tendons between segments, which is more realistic as this is how a real brittle star’s body is constructed. This option is however not used by the controller and morphology departments, as the substantial increase in MuJoCo physics objects (and trainable parameters) made it unbearably slow for us to train.

Environment

The main task of the environment is to expose tunable parameters to the other domains. Morphology optimization uses these parameters to e.g. increase the disc size, tweak the number of segments per arm, … whereas controller optimization uses e.g. wrappers and configuration parameters to extend the environment and to set the target location.

Some of the most important changes include a more realistic environment, all kinds of manipulations for the target position,

exposure of important functionality and the integration of HD-quality cameras.

Realism

To make the simulation more realistic, we changed the medium of the simulation to water - i.e., we increased the density to 1.000 and the viscosity to 0.0009. By doing this the brittle star lost the ability to jump around in the medium (which it shouldn’t be able to). MuJoCo also allows us to create currents using wind. However, we did not have enough time to experiment with this in training, so it remains unused.

Target positions

The simulation environment provides multiple parameters to control the location of targets. First of all, the distance from the origin can be set. Knowing that the robot spawns at the origin, we can conclude that this is also the distance to the robot. By setting this parameter the rotation of the target is randomised but the distance will remain the same.

If the controller optimization wants to randomize this location, they can provide a range with a minimum and a maximum value. The target will spawn at a random angle but at a distance in the provided range.

A final way to set the targets is by placing them along a circle at a certain distance. The radian of this circle can be set by the previously described arguments, but only the initial angle of the first target will be randomised. The gif below this paragraph gives an example of a circle with a radian of 5 and with 5 different target locations. The angle of the first target will be between 0 and 2*π divided by the number of target locations.

Miscellaneous functionality

We have added numerous extra parameters to allow the controller optimization department to work more freely. One of these is an option to wrap the entire simulation environment (which is usually not accessible) in order to further customize it.

The reward function has also been adjusted to no longer include the z-angle to the target. As a real-life brittle star has no “front” or “back”, it does not rotate towards its target. This is one of the main goals of our research. By removing the angle from the reward function, the controller is not inclined to rotate anymore. When this reward function would not be good enough, we allow them to easily pass in their own custom reward functions to get more fine-grained control over the rewards.

There are dozens of extra parameters, but we can’t name them all. Most of these serve to glue the morphology and controller departments together smoothly, and give the controller optimization the ability to customize (or replace) internal functionality.

Cameras

The simulation environment adds two cameras so that we can record our findings in an efficient manner. This means that for the normal locomotion environment there are now 3 cameras, the first (index 0) is the free camera, the second (index 1) tracks the brittle star and the third camera provides a top-down view of the target.

Our other environment, the Terrain Generation Environment, only has the last two cameras. For this environment the indices are 0 and 1 instead of 1 and 2.

The quality of these cameras is set to 1920x1080 (1080p) during the initialization of the environment. When rendering a video one can pass the width and height parameters to the render method to actually record with this quality.

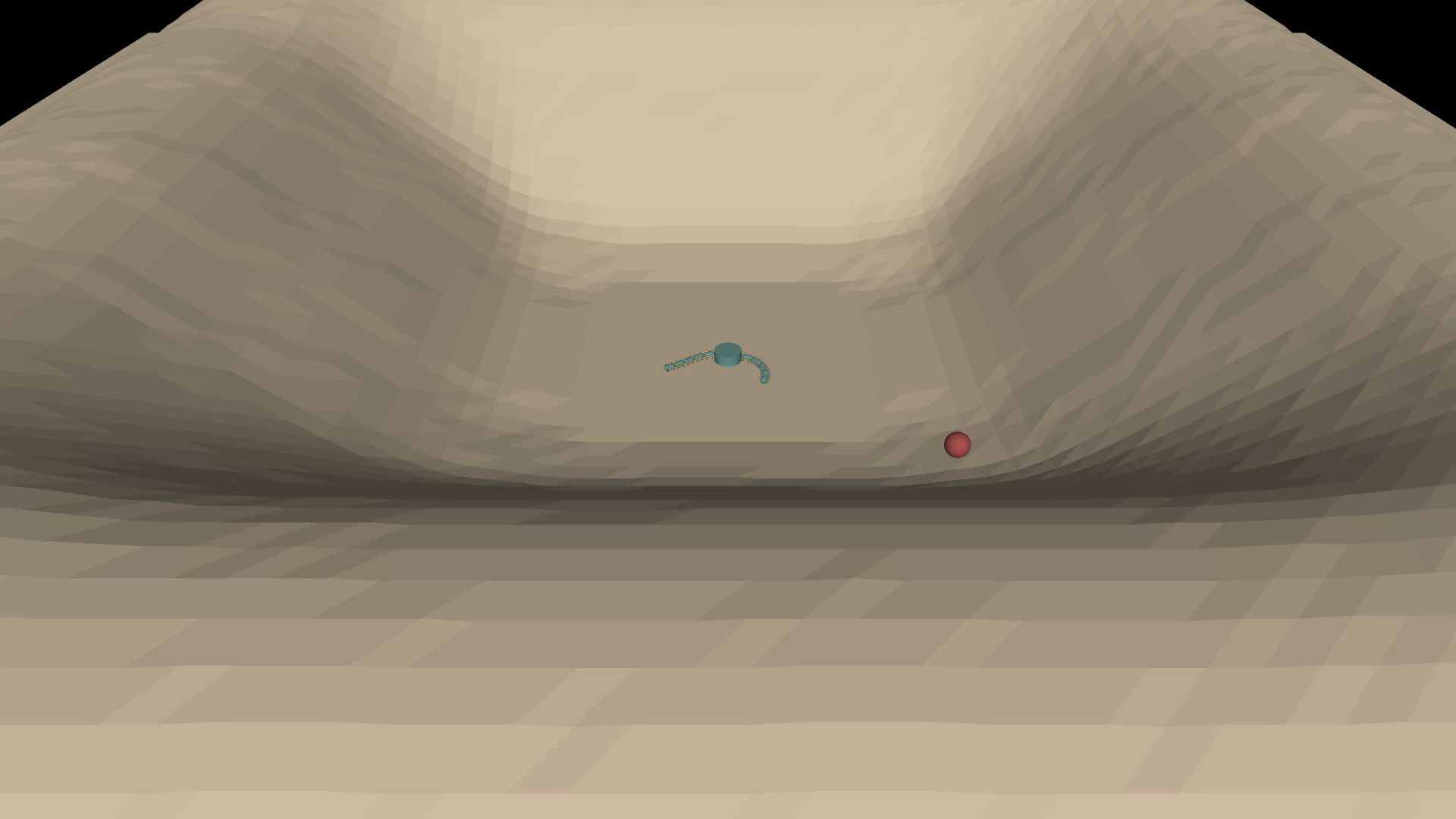

Camera that tracks the brittle star (1920x1080):

Camera that gives a top-down view of the target (1920x1080):

Terrain Generation

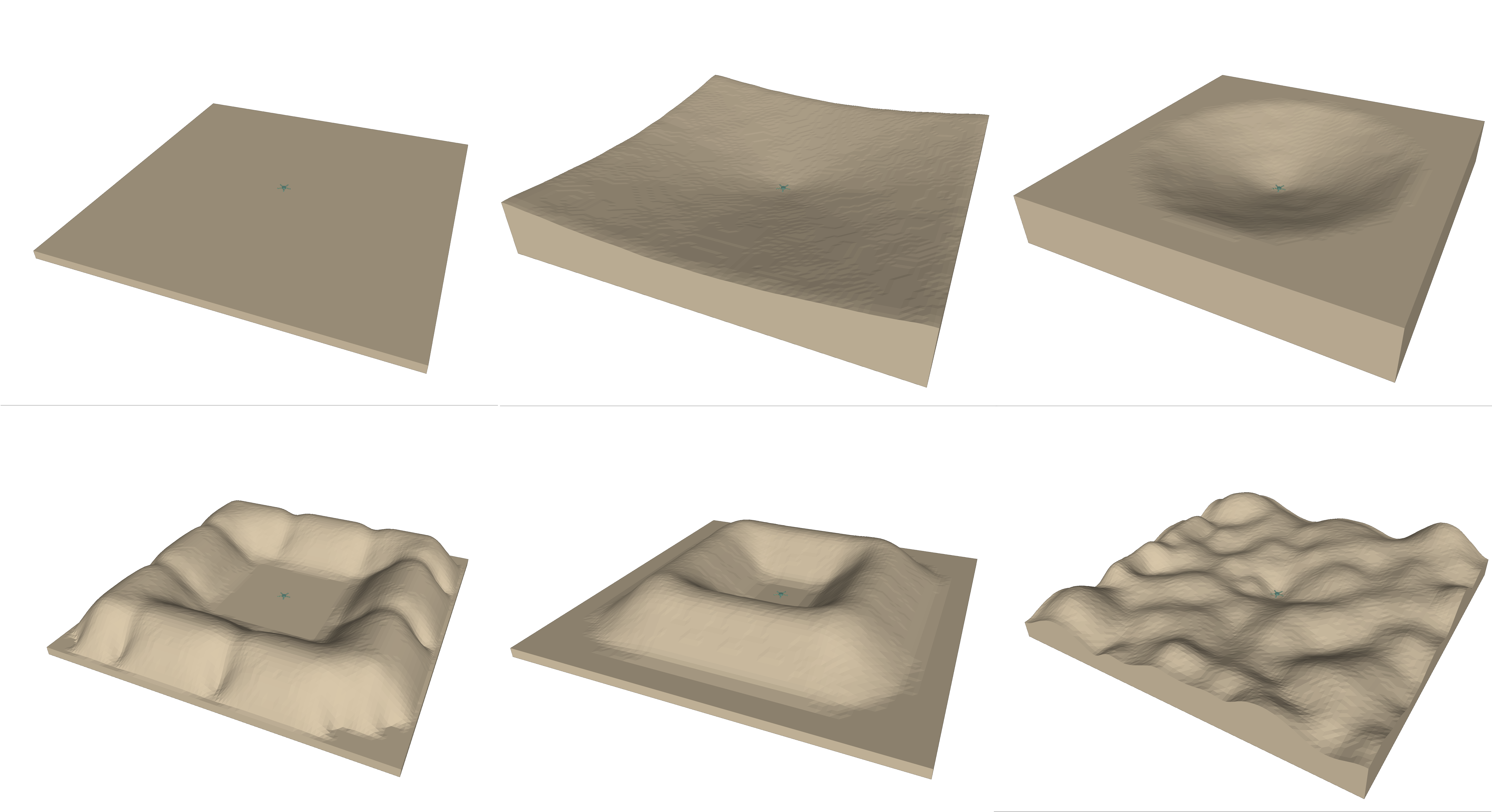

Apart from the original LocomotionEnvironmentConfig we also provide a TerrainGenerationEnvironmentConfig. This configuration class returns an environment with a custom terrain. These terrains can be provided by the user as .png files, containing top-down greyscale images of the terrain.

The user can either provide these individually or as a folder. If a folder is provided, a terrain map will be chosen randomly from the folder.

Another possibility is random generation, these maps are generated using perlin noise and can be used to make an infinite amount of random terrains. By using perlin noise as opposed to full randomness, the difference between adjacent pixels is minimized to avoid steep climbs or drops. This technique is often used to generate random terrain in e.g. video games or 3D software.

We also provide 6 default heightmaps that are ordered by increasing difficulty, the size and height of these maps can be adjusted by providing the correct arguments to the TerrainGenerationEnvironmentConfig. This allows us to make a map as easy or difficult (steep) as we want to, and push the robot to its limits. All of these are generated with .png images that can be found in the simulation environment repository.

In order to avoid clipping into the floor, we interpolate the position and corresponding height of the robot and target, and spawn them slightly above. In edge cases where the robot would still clip into the walls (e.g. very steep pits), it’s possible to provide a parameter to increase the spawn height even further.

CLI, JSON schemas and builders

To ease the process of making a robot and environment with the required specifications we added a CLI, builders and a JSON schema. The CLI provides commands for generating heightmaps and XML files for MuJoCo from a JSON file. You can use what we call “specfiles” to create custom XML files. More information can be found in the CLI documentation in our GitHub repository.

The creation of these specfiles is simplified by the provided JSON schema. This schema provides the user with autocompletion and linting for the JSON/specfile in their IDE. Needless to say that this speeds up the creation of these files tremendously.

To do all of these things we use so-called builders, responsible for translating the provided JSON file into an actual robot. They provide default values and create the necessary parts to form an actual brittle star.