Morphology

The Body

When we started with this project the robot could only change it’s body by mutating the stifnesses of the joints. These changes influence how the robot can move, but these are not visible the the eye when ignoring the movement. We had set a few goals for ourselves to make the robot more modular in following ways:

- Mutable number of segments

- Each segment should be able to modify its dimensions

- The central disk should be able to change dimensions to increase performance

These goals are achieved using a graph representation. By doing this we can iteratively unfold recursive loops and add or remove segments with ease. This allows the robot to shape itself based on how it performs. Having this indirect genome encoding also allowed us to modify easily only train 1 arm and use this same arm on the whole robot. This makes sense from a morphological standpoint since the brittle star can use each of its arms as a front- or trailing-arm. This simplification also greatly reduces the number of parameters to train.

Ultimately we ended up optimizing following parameters:

- Disk

- Radius

- Height

- Segment

- Radius

- Length

- Joint

- Stiffness

- Range

- Damping factor

- Tendon

- Contraction factor

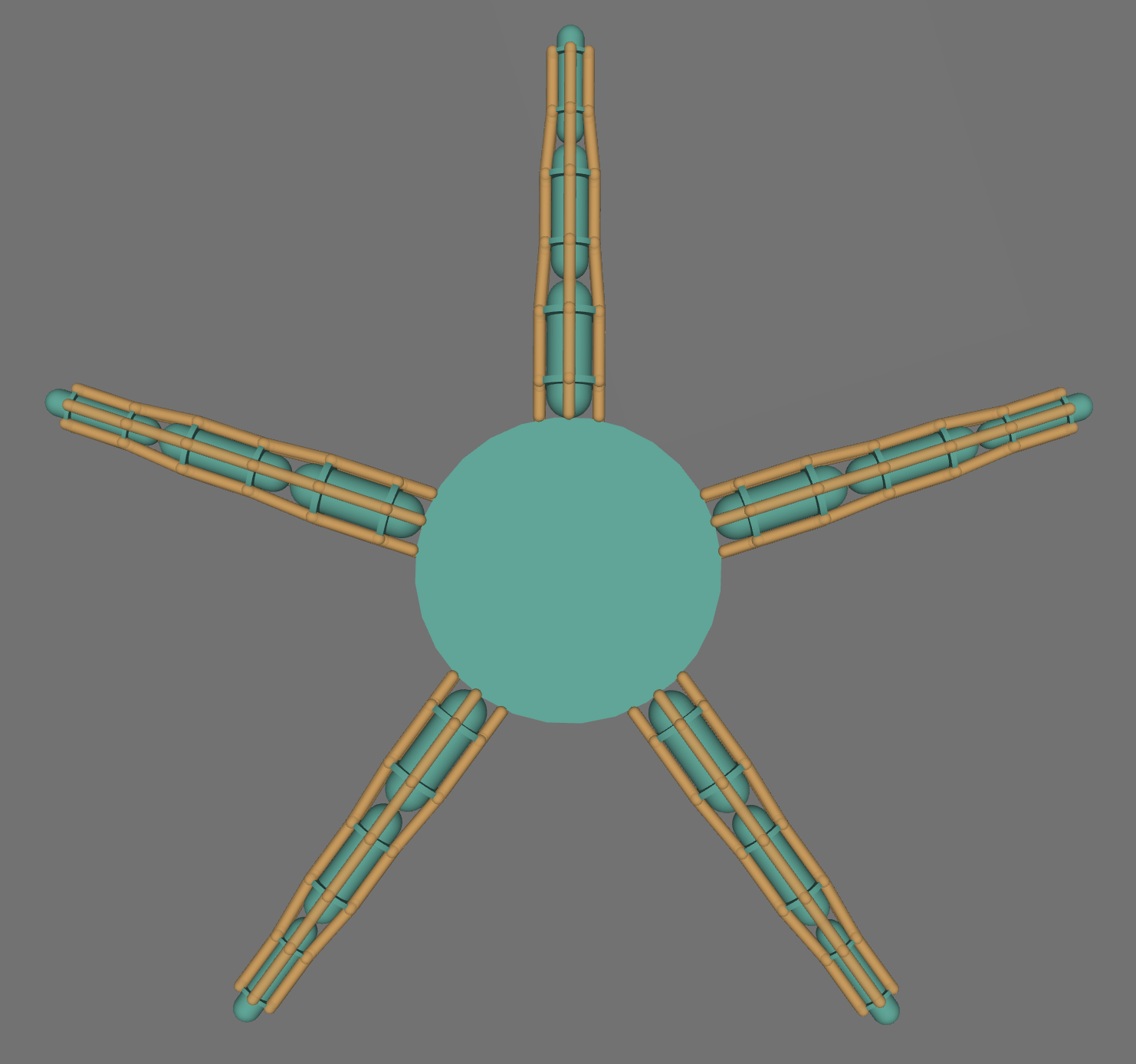

- Stretch factor

During training we give complete freedom to how it should be shaped. Based on how a brittle star looks in real life we expect that segments further away from the central disk become smaller. This is indeed something we see after training.

Keep in mind that this is the result of 1 training. Not every run produces this exact result. We’ve also noticed some runs where the end of the arms is a bit wider, but never in a major way.

CPG

Cartesian based

The CPG is the part of the robot that makes a basic forward movement we can give to the controller optimization.

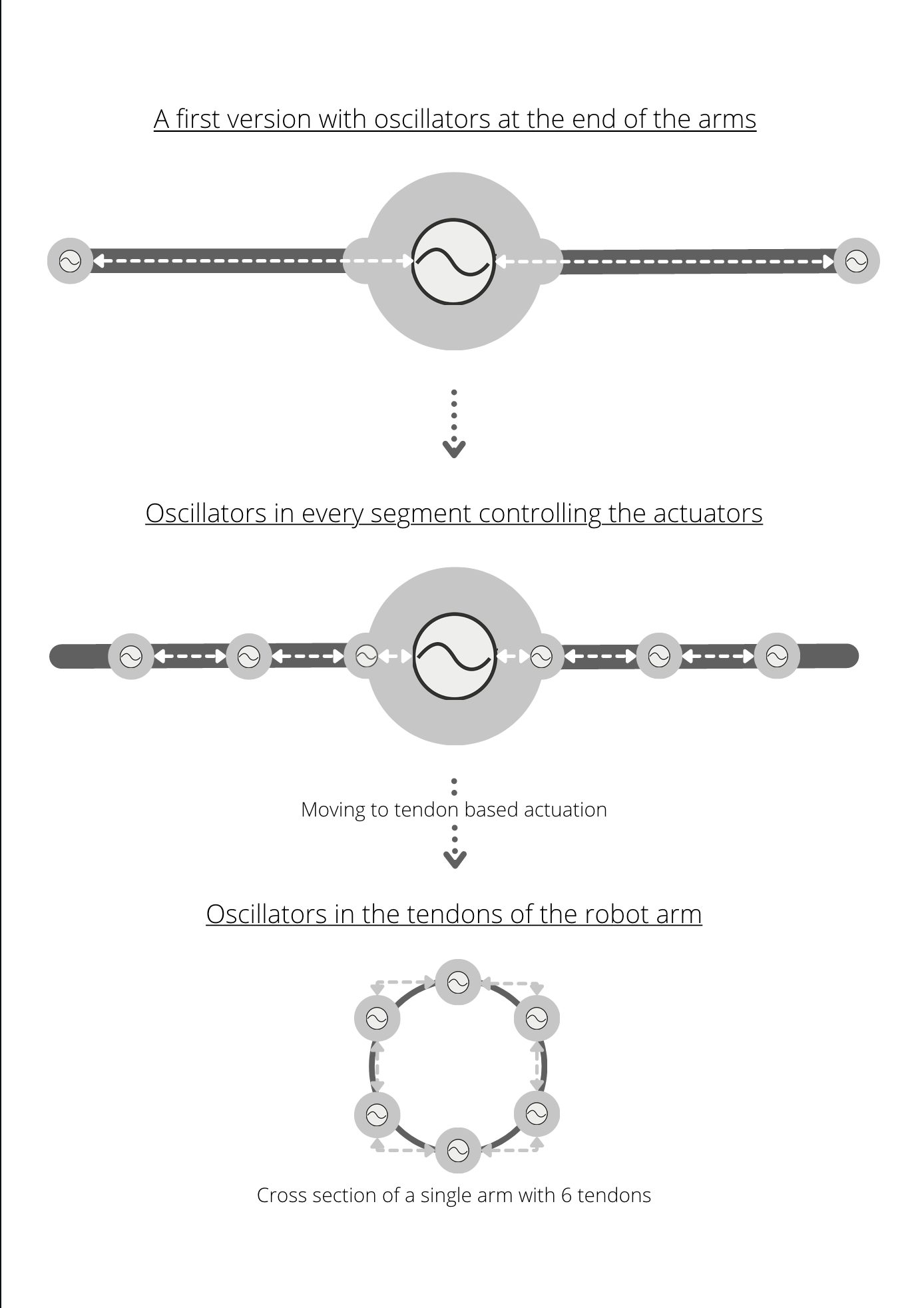

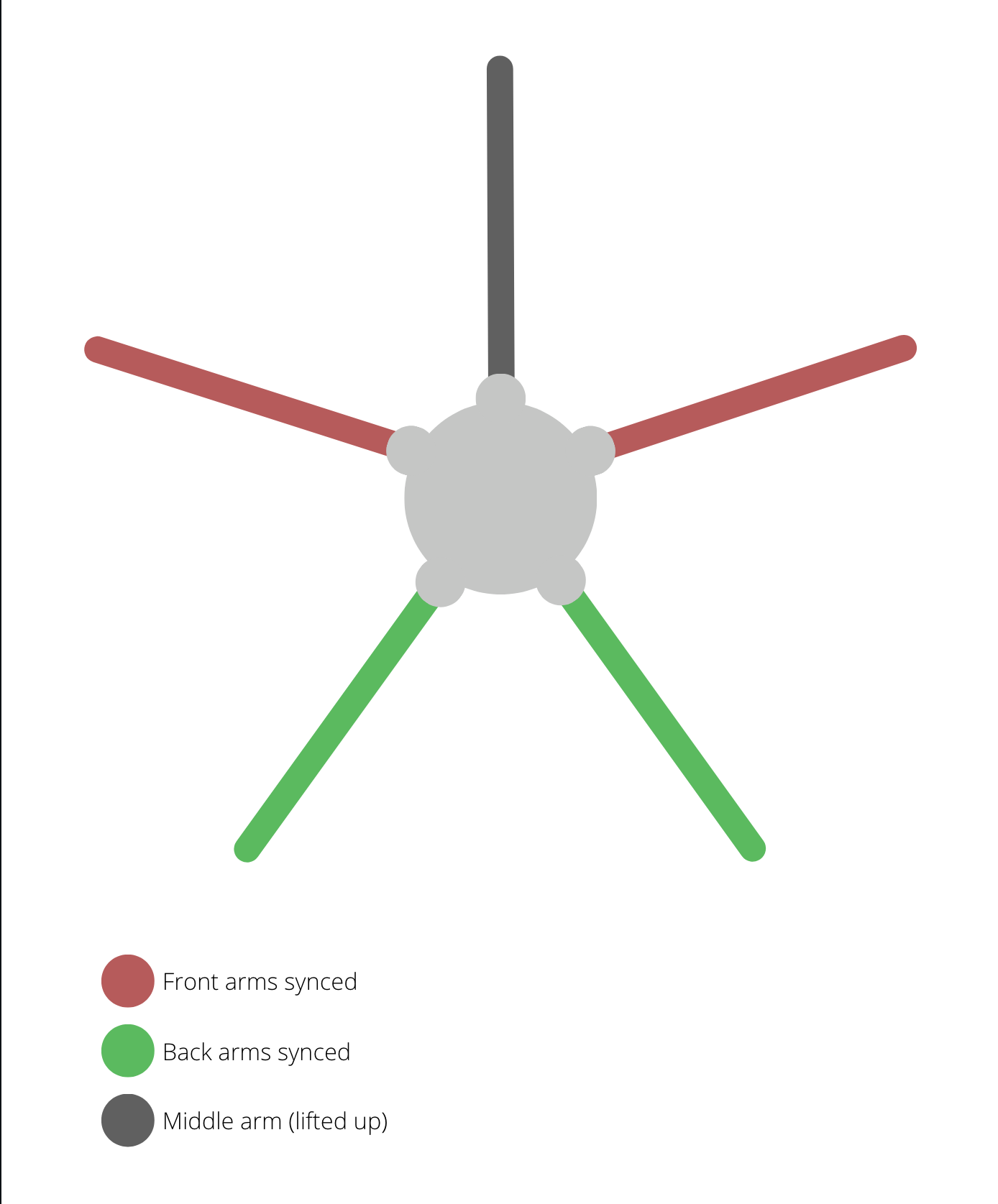

We started with a basic implementation of a CPG that was inspired by the paper “Learning to Move in Modular Robots using Central Pattern Generators and Online Optimization”. In our first implementation when we where working with a cartesian we used 2 oscillators per arm to move in both the x and y direction. We also had a master oscillator in the disk of the robot to delegate the movement of the arms.

Tendon based

To have a more realistic robot we moved from our cartesian representation to a tendon based approach. In this implementation we added an oscillator per tendon who are connected in a ring like structure. This way we can have a more realistic movement of the arms. We also kept the master oscillator to the disk of the robot to delegate the movement of the arms. Because we want our robot to walk in a straight line we mirrored the oscillators of the arms on the other side of the robot.

Smoothening

To have a more realistic movement of the arms we added smoothening when the requested amplitudes change. This way the movement is not abruptly changed but transitions smoothly to the new amplitude. In the following video you can first see the robot moving forward and then the right arms are ordered to move backwards. You can see that the movement of the arms starts to slow down and then moves backwards.

The evolutionary algorithm

Our evolutionary algorithm has a few features to increase the performance of the genomes over time.

Mutation

This was given by the start code and further improved with our extra additions to the body and CPG.

Cross-over

We added this to enable the possibility of creating new genomes that are a mix between 2 parents. This is part of a standard evolutionary algorithm but was not yet implemented in the beginning. Because of this, this was 1 of our first steps in improving the evolutionary algorithm.

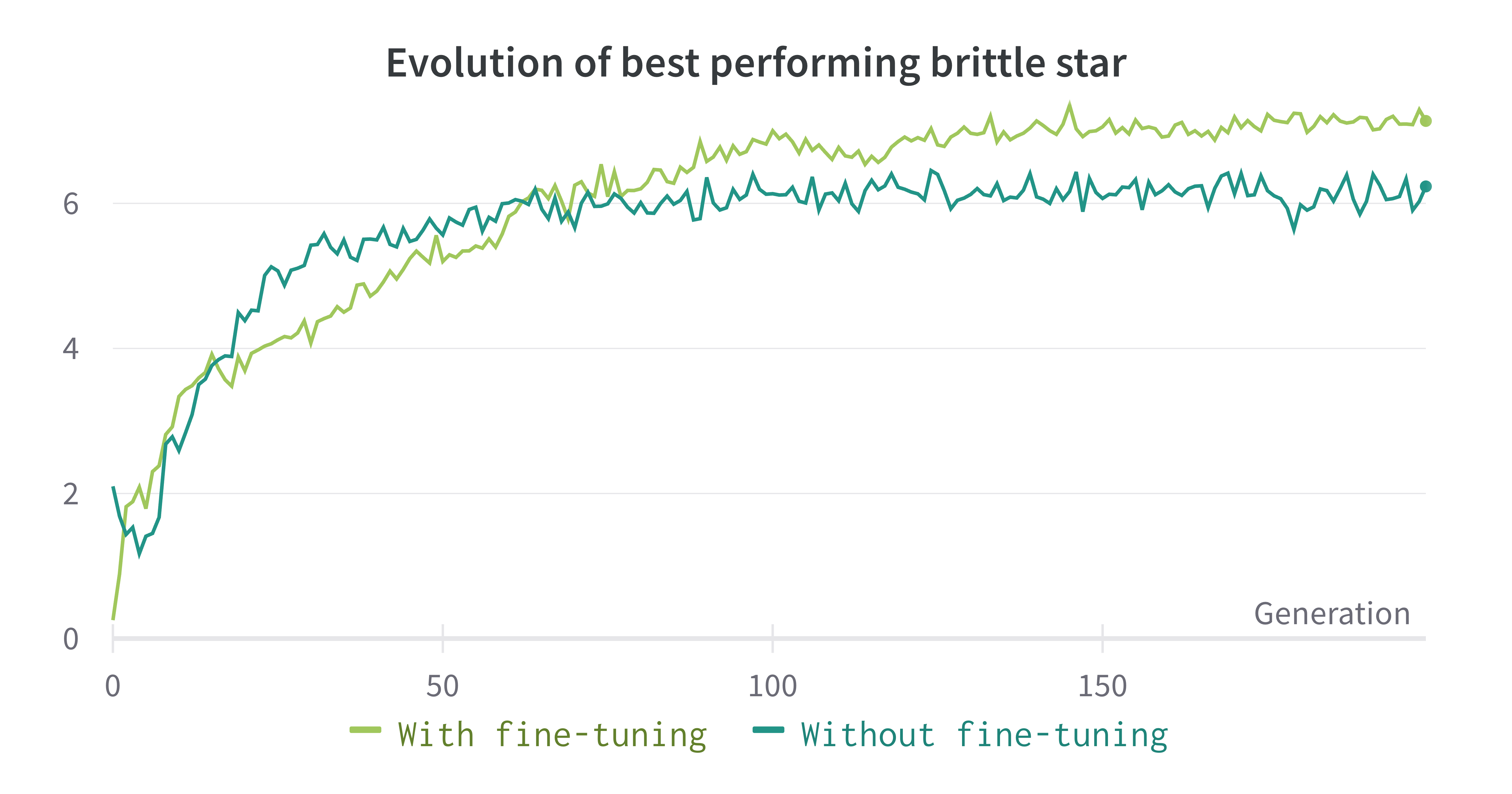

Fine-Tuning

We noticed that later on during training we kept making big steps in how we mutated the genomes. This is not wanted since later on in the evolution the body has already evolved to a better place. To make optimal use if this we decrease the mutation size during evolution. This has the effect that we only make small precise changes at the end of the evolutionary algorithm. This improves the performance of the resulting robot.

This is visible in the graphs in the fact that with fine-tuning the performance stays more stable at the end (smaller jumps up and down) and it also takes longer for the robot until its performance reaches a plateau. While without fine-tuning we initially have better performance. This is because decreasing the mutation size (even a bit) in the beginning can have a significant impact on how long it takes until the robot has reached a quite stable place.

Multiple environments

We can optimize our robot for 1 specific environment, but what happens if we attempt to optimize for multiple environments?

The resulting goal is to create some jack of all trades, master of none brittle star.

This is what we attempted to do.

The main idea was to not just perform cross-over on the best robot of 1 environment, but to do this on the best robot of the multiple environments that we are training on.

This way we try to keep speciation in the population (since a robot that performs well on flat level, might look different than a robot that performs well on a hilly level).

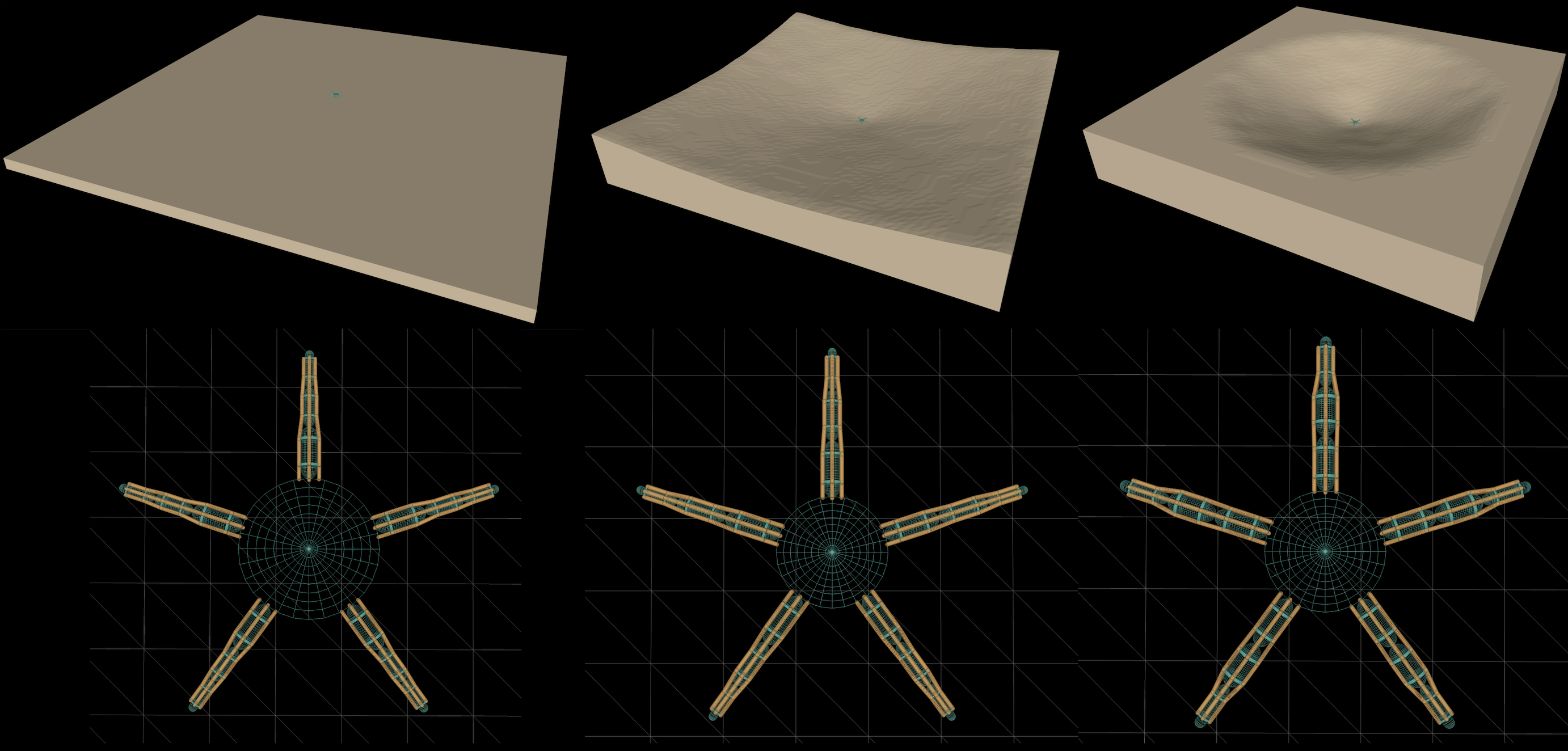

Unfortunately, this experiment did not deliver any noteworthy results. As shown in the image below, even optimizing the robot separately on 3 different levels produces very similar results.

We also create a video that shows how each robot moves in the environment it was trained on.

Results

It is really hard to draw strong conclusions from our testing since our equipment to execute all these tests is very limited compared to the runtime of the code. Optimizing 1 morphology + CPG for 200 generations takes around 1.5 hours on a M1 Pro CPU with 8 cores. Because of this it is not feasible for us to train large amounts of robots (with different seeds) and take the average of all of these runs.

However, here are some things we noticed:

- Fine-tuning improves the final performance but the robot takes longer to reach its optimal configuration

- The robot prefers a large and thin disk in combination with quite short arms

- Training on different levels does not have a huge impact on how the robot looks physically. The arms might have slightly different shapes but not by a lot. Mainly the CPG differs with a pattern that is a bit slower or faster.